This is a Test

Forever Falling Down Stairs

What is it like to live without forming new memories?

I met a few people while running art projects in hospitals and care homes who, every few seconds, needed to be reminded of where they were and what they were doing. One of them, Paula, had to be told that she was safe and in the right place constantly, or her head would tilt back, her eyes would lose focus, and she would start to scream. I thought it might help if I held her hand, but it made no difference. All I had to do was stop talking to her and she would zone out or start to shout, “What am I doing? Please help me!” Playing her favorite music occasionally helped, but she would need someone to sit with her and remind her to listen. In truth, her life was lived in a state of almost constant panic. The care staff would dress her and help her eat. She could use cutlery, but without being reminded every few seconds, she would drop the food on the floor and start to scream. Inevitably, she would be returned to her room soon after getting up, hoping she might fall asleep.

In 2003, a social worker asked if I could arrange visits to an elderly woman living alone in Earls Court. He mentioned that she had a very poor memory, was depressed, and resistant to care. She had been an artist and he thought she might enjoy participating in the arts outreach service I ran for Age Concern. He said he would call her a minute or two before my assessment visit to let her know who I was.

When I arrived, she said something like, “You must be David. I’m so sorry you’ve had to waste your time. I’m fine. I don’t understand why they keep sending people”. She invited me in. The flat was clean and tidy, and she was well-dressed. She made us cups of tea, and we talked for 20 minutes about how Earls Court had changed since she moved to the area in the 1960s. As I was leaving, she apologised again, said she enjoyed our short chat, and wished me luck with the project.

I called her social worker immediately after leaving and told him I saw no evidence of dementia and didn’t think she was a good fit for the arts visits. He suggested that if I had time, I should go for a coffee and return in an hour, promising to call her to let her know I was coming.

Astonishingly, when I went back, she invited me in again and apologised for wasting my time. She washed the mug I’d used an hour earlier, made more tea, and told me how Earls Court had changed since she moved there in the 1960s. She didn’t remember my previous visit at all.

I met Liza a year later when I piloted the arts outreach service in care homes. She was in her 80s, tall, university-educated, and had a sharp wit. Her boyfriend visited most days, and they would chat and laugh together. Liza shared stories about her children - Dante, Gabriella, Justin, and Francesca - as well as her childhood in Edinburgh. Conversations with her were easy and fun.

One day, she decided to join a reminiscence quiz where we used enlarged photographs of famous people. I provided clues to help the participants guess who they were. The quiz was mainly a way to encourage a bit of conversation. Liza excelled at it, especially with stars from the 1950s and '60s, though, noticeably, she couldn't remember anyone from the '70s or later.

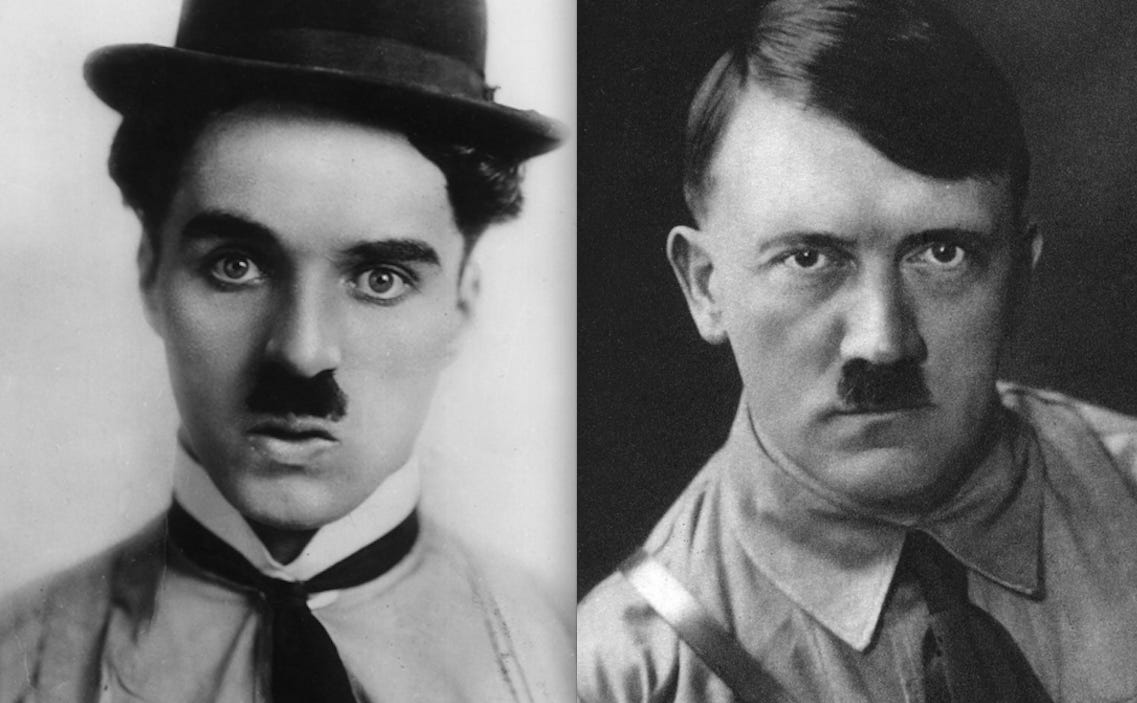

During the quiz, I held up a picture of Charlie Chaplin, pointing out his distinctive moustache, bow tie, and bowler hat. A few participants confidently guessed, "It’s Hitler!" We then discussed Chaplin, and Liza said how badly McCarthy had treated him. After a moment, I placed the card face down on the floor. About a minute later, I asked Liza if she remembered whose picture it was. She replied, "How could I know? I haven’t seen it yet”.

Liza’s boyfriend started to laugh, and I found it a bit strange, thinking she might be joking. So, we went through the small group of photographs again. I placed Chaplin's picture face down on the floor and asked everyone to try to remember who it was. This time, I waited about half a minute. Again, Liza couldn't recall whose picture was on the card. She wasn't worried about forgetting; she genuinely had no memory of having seen the picture before.

I tried one more time, laying the picture of Chaplin face down on the carpet. I counted to ten and then asked Liza to guess who was on the card. "It’s Hitler," she said.

The following story was told to me by Liza and maintains her words:

My Children All Have Good Names

“I like your shoes. They make your feet look a bit on the huge side. They’re like a clown would wear. I don’t mean that at all really. Some of the people here are bloody awful, so I say things to wind them up. We’ll have them tossed out of the window! They’re well above themselves, they think they’re on top of the world. And they’re very aloof. I can’t remember who they are anyway, and they know that.

“I was born in Edinburgh and my mother sent me to a good fee-paying school, Gillespie High School. That was in Morningside. Do you know I can’t remember when I was born? I grew up in a place called Spring Valley Terrace. I never ever enjoyed school, I always hated being locked up.

“I was always keen on the idea of university but I don’t think I ever did anything seriously. I was at this, that, and the other. I was good at composition, I used to love to write, to make up stories about Morningside. I may have had one or two things published. It was my teachers who did it for me. I never had a good memory, I think it’s always been bad. But I was good at composition, and I won prizes. Good at writing, bad at the higher arithmetic. I was in amongst the top measure of the year for my writing. It was a good school, a fee-paying school which was good for her because she was a widow. She had to work, her husband was killed in the war. I know my father had some kind of collision. She worked hard to keep us there, me and my brother, we were in Spring Valley. I haven’t a clue what happened to my father, I think it was something to do with the war. I never remember my dad at all. There were lots of photographs. He wasn’t a bad looking bloke.

“There were two of us, me and my brother, Arthur William Bryden – Billy for short. And I was Liza Dalrymple Bryden. That was our native name – our relative name, family name. My mother put me on it.

“I remember playing in the street, up at Spring Valley Terrace, where I lived, where all the children played. Spring Valley Terrace, a big wide street with houses on either side, a wide road to play in. We had a good old time down there, got away with everything. I had a happy childhood, though my father wasn’t with us. They divorced, the marriage broke up. He was a rotten egg, I think. I never really knew him too well. My mother worked hard to bring us up. A very good woman she was.

“Mother, she sent us to a fee-paying school. She worked hard, she didn’t have much fun out of life. How could she have if she was working all day every day? It was mainly to do with restaurants. She had a mix of jobs, she had a good status, well respected. She was a good woman, she sent me to a fee-paying school. My mother was a widow, she was working hard. She was a good woman. I can’t remember any hits or anything like that. She was a tall healthy-looking woman. She was working for her children, keeping them together. My father was a rotten egg. He was an Englishman. My mother was Scottish and my grandfather was German.

“My mother was very good to me and my brother, but my brother was a bastard, a bastard, my dear. He didn’t like me being there at all. He was my mother’s pride and joy until I came. He took up the major attention. She was a very good woman. Her husband was a rotten egg, he left her. I think he left her. I don’t really remember much about my father at all. I never really met him, I don’t think.

“I remember my grandmother but not my grandfather, he was killed in the First World War. My grandmother, she was a very, very good woman, never lashed or anything like that, very sweet she was. My grandmother looked after us while my mother did her job. We were sent to a good fee-paying school. My grandma loved her church. I went to Sunday school, but it wasn’t for me, I was made to go. Church was a very important business as far as my parents were concerned.

“The only person I didn’t really appreciate was my brother, because he didn’t appreciate me. My brother unfortunately was a victim of the war. He was part of the artillery. My brother was injured, but he was at home. My brother’s name was Billy. He was the only child until I came along, then I took my mother’s attention, because I needed it. I was young, deeply reserved he was. That was the sort of feeling he’d got, resentment towards me, towards me being there. I didn’t like him and he didn’t like me. I think it disappeared as I grew to my later teens. I never had much contact with him, we never went out together.

“I must say that when I first came to London I got a downfall. Dirty bloody streets, buses, crowds and gloomy looking. I can’t remember why the hell I came. I was amazed when I came to London and got out at King’s Cross. I thought it was appalling, it was full of heavy traffic. There’s a lot of space in Edinburgh. I can’t remember why I came to London. I just thought it was the done thing to head off to the Capital. I came to London when I was in my teens and I wasn’t terribly impressed because, you know, Edinburgh is a city full of spaces, lots of traffic and the same is true of London. In fact London looked a little bit run down, it seemed over full of people even then. Edinburgh is a more good-for-looking-at city, that’s what I thought. Shocking, I had some of those feelings. It’s not a very good spot, not very picturesque.

“I can’t remember at all what I did when I left school. I’m pretty certain I wasn’t a teacher. I never cared too much for work in any form. I did just as much as I had to. You know, I can’t remember much. It’s upsetting. I can’t even remember why I’m here. I think there was a bit of war going on, but who the hell knows?

“I married Patrick Quinn. I’ve not thought of him for years. My husband was a good man. He was an Irishman, a good man. He’s dead. All this seems very vague to me. Patrick Quinn was a very good man, very sensible, very bright. My children all have good names: Francesca, Gabriella, Dante and Justin. I liked the sound of them. We had five kids, Francesca, Gabriella, Christopher, Pieta. I don’t know where they all are at the moment, they’re somewhere.

“Some of these idiots know that they can take the piss. I know they take the piss. I can’t stand this fucking dump. I really don’t know why I’m here. I can’t remember anything so they don’t take me very seriously. I’ve got a shocking memory. I never had a good memory. I think I was told that my father abandoned my mother at some time – no, he died. He died in the war, so he wasn’t there.

“I’m afraid I don’t remember. My memory is shocking, I’ve got a very bad memory. I never had a good one. It’s like forever falling down the stairs.”

Wow. Again.